EVALUATE YOUR PROJECTS

In the previous post, we covered the detailed steps for building a prioritization scoring model. In this post we will cover the steps for how to prioritize projects with a scoring model.

Step 4 – prioritize projects using scoring values

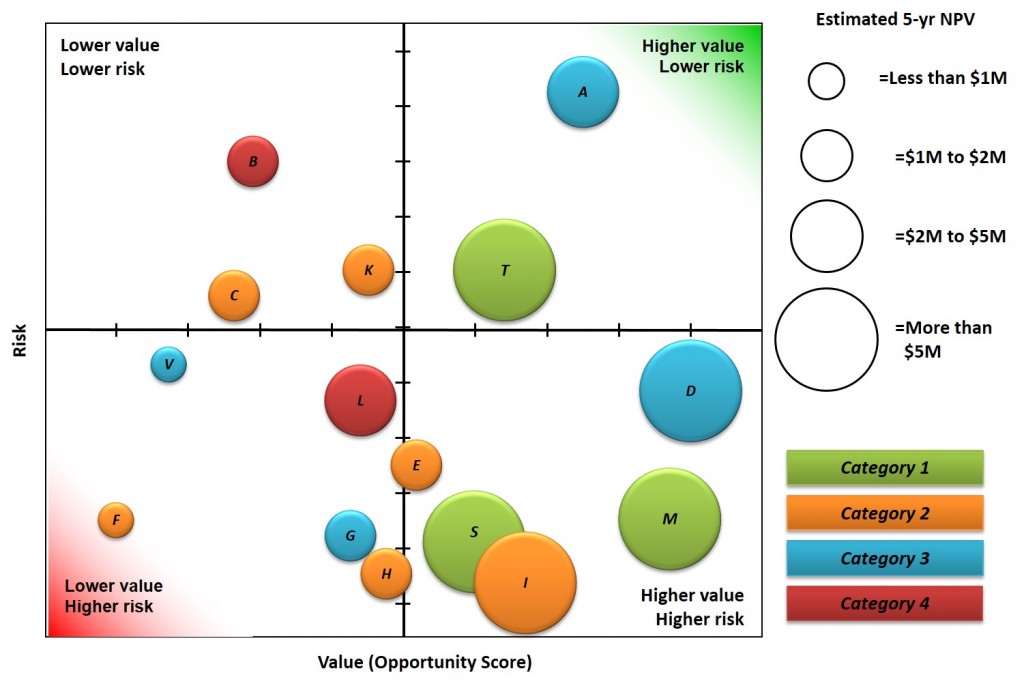

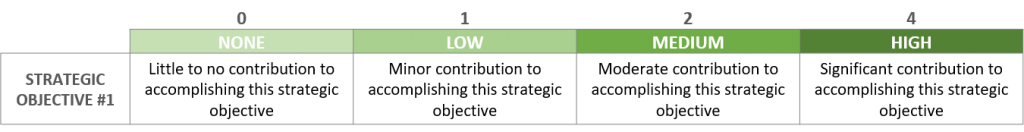

The last part of the scoring model is to determine the scoring values. For each criterion in the scoring model, there needs to be some evaluation of a low, medium, or high score to drive a numerical score for that criterion. In practice we can expand this to “none”, “low”, “medium”, and “high” to give the decision makers a slightly wider range of options. We do not want too many options as this can slow down the scoring process, but we want enough options to help distinguish project evaluations. A common scoring paradigm would include 0 for none, 1 for low, 2 for medium, and 4 for high. If companies want to put even more emphasis on high value, they could use a 0, 1, 3, 9 scoring paradigm.

In the example below, each of the four qualitative values has a corresponding quantitative value. For each value, there is a definition to help determine to which value the project best aligns. If the governance team determined that a particular project has a medium alignment to strategic objective #1, it would score a 2. This is an important step for decision makers to prioritize projects and we will explore all of the calculations at the end of this post.

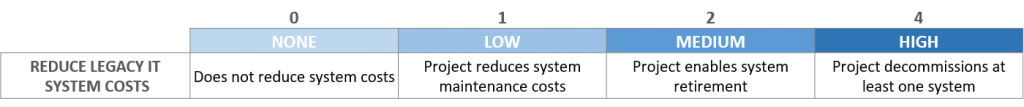

The definitions alone can significantly improve the quality of the project scores. The example below is relatively generic and requires the governance team to possess enough knowledge about the project and the strategic objective to properly determine the degree of strategic alignment. This can be problematic if the governance team “feels” that a given project has moderate to high alignment and therefore warrants a higher score. The scoring process is intended to make the prioritization process as objective as possible. This can be accomplished by more specifically defining the underlying criteria of “none”, “low”, “medium”, and “high”. In example #2, an IT department of a large Fortune 500 firm has a specific strategic objective to reduce the number of legacy computing systems. The criteria for each of the four options is far clearer with little need for interpretation. If the project actually decommissions a system, it scores “high”. As companies mature their evaluation process, the specific criteria for none through high can be enhanced.

For financial evaluations, it is important to set financial thresholds that will really set the winners apart. If the bar is set too low, too many projects will get “high” scores and the scoring model won’t be of much help to distinguish the highest value work.

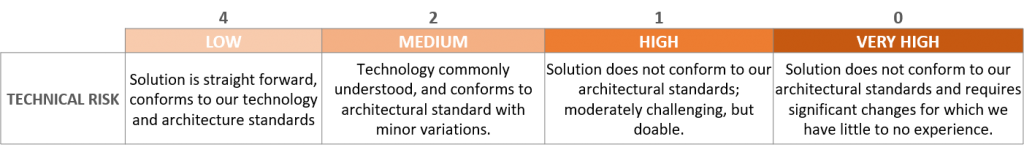

For the riskiness evaluations, we need to flip the quantitative values so that the highest number corresponds to the lowest risk qualitative value. By doing so, we are giving more value to less risky projects. This makes sense especially if we have two projects which may be nearly identical in value but one is far riskier than the other; under normal circumstances if we could only choose one over the other we should choose the less risky option (i.e. better risk-adjusted value).

For a free copy of these slides, sign up now.

Step 5 – collect all necessary information in order to prioritize projects

In order to evaluate projects or new proposals, some amount of information is needed to understand the scope, importance, alignment, cost, benefit, and risks of the project. Based on the actual scoring model you built and your current organizational processes, you may already have all the information you need to use the scoring model. In other cases, new information needs to be collected. Let’s break it out in further detail.

Strategic information: at some point during the intake/proposal phase, the project initiator for each proposal should have provided some rationale for how the proposed project aligns with one or more strategic objectives. Simply stating that alignment exists is not useful; there should be an explanation of how the project supports the organization’s strategic objectives. This information should be captured in a document for each governance team member to review. If this information does not exist (or does not exist for all current projects), the Project Sponsor can help explain strategic alignment when the governance team evaluates the projects. If most current projects are missing this information, the Project Management Office (or other team facilitating the prioritization process) should update organizational processes to include this information going forward.

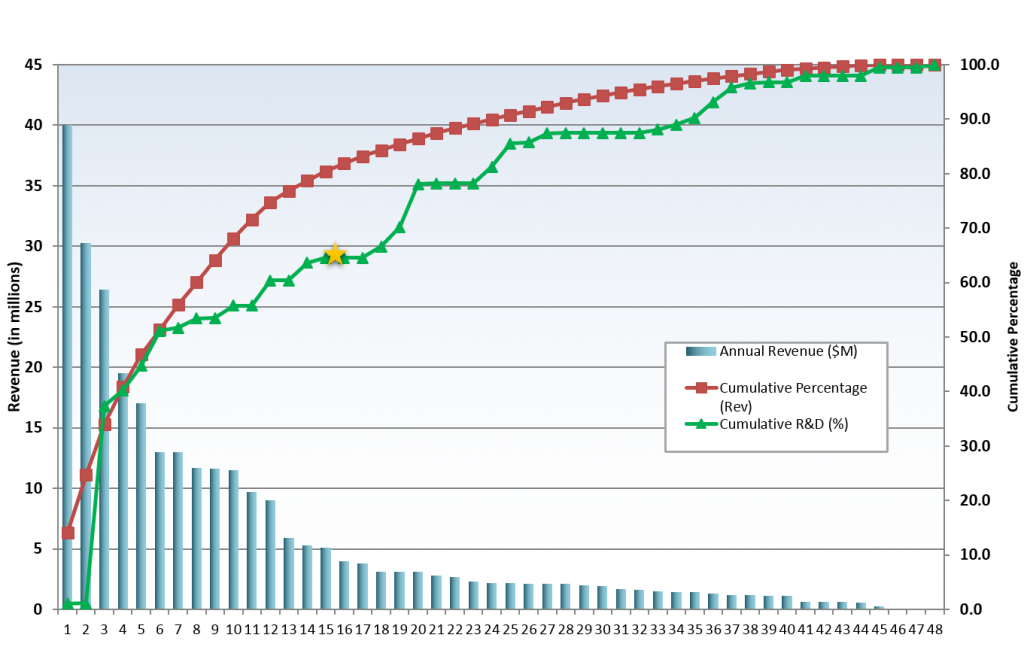

Financial information: assuming that your scoring model utilizes quantitative financial information, it is very important to ensure that this information is available for all projects (a common challenge for many organizations). The best approach is to work with the Finance department to do some level of financial analysis to determine financial benefits for each project. This will lead to consistent financial information across the portfolio. Without Finance’s help, most organizations struggle to get meaningful financial benefits. The best alternative to getting Finance’s help is to provide spreadsheet templates to each project team to assist with calculating the financial metrics used in the scoring model.

Riskiness information: information about the inherent riskiness of the project is useful for conducting this evaluation. It is important to keep in mind that this assessment is not about the specific project risks (although this could be useful), but about the inherent risk nature of the project. Answering questions such as: “how much organizational disruption will this project cause?” “How much experience do we have with this type of project?” “Do we have a sufficient skill set internally to deliver this project?” are important to evaluate the riskiness of the project. Ideally, some of this information is contained in the business case, project proposal form, or even in a project charter.

Step 6 – Educate stakeholders on how to prioritize projects

Everyone involved with evaluating and scoring projects must understand the relevant details of all projects in the portfolio in order to successfully prioritize projects. If your scoring model includes a strategic component, financial component, and riskiness component, we recommend the following roles for scoring projects:

- Strategy: The Governance Team, representing the senior leaders of the organization is best equipped to evaluate the strategic value of each project

- Financials: this is easily derived from the financial analysis and no additional evaluation is needed. A Portfolio Analyst or PMO Administrator should be available to compile this information and capture it in a single data repository.

- Riskiness: The Project Manager or PMO Director will be in the best position to evaluate the riskiness of a project. The PMO Director could be the singular person to evaluate riskiness across all projects in the portfolio, which streamlines this evaluation. Alternatively, each Project Manager could evaluate and score individual and share the results with the Portfolio Analyst or PMO Administrator. A group of Project Managers could come together and work together to score their projects as individual Project Managers may interpret criteria a little differently.

In most cases, this requires a certain level of education so each project is fairly evaluated. This is not a small effort. Although the Governance Team may be sponsoring some of the current projects in the portfolio, they won’t be familiar with all of them. That will affect the team’s ability to evaluate and score the projects. Therefore, some level of education is needed to bring everyone up to speed. There are a few ways to accomplish this:

- Prepare summary information of each project for the Governance Team to read on their own before the meeting (examples include: business case, charter, etc.). The advantage of this approach is to expedite the scoring exercise.

- Prepare summary information of each project for the Governance Team to review during the meeting. Using this approach, the Governance Team would likely review a batch of projects and score them in the same session. The advantage of using this approach is that everyone will have dedicated time to review project information and discuss as a group. This option also takes longer than option 1.

- Conduct mini project reviews in a team meeting with the Project Managers in attendance to present and answer questions. The advantage of this approach is that it gives the Governance Team an opportunity to ask important follow-up questions as well as get to know the Project Managers better. This option takes longer than the previous two options.

Step 7 – Evaluate and Score

Tips for handling the evaluation and scoring:

- Pilot the scoring with a handful of projects: pick a few representative projects (projects known to be high priority and lower priority, across various strategic objectives)

- Conduct the pilot with the governance team in person: even after prioritizing criteria and discussing it as a team, there will still be questions about specific projects and how they align to the strategic objectives.

- Build in adequate time for discussion: there will be different degrees of understanding of the projects and some projects will require more discussion than others. The value is in the discussion, so build in adequate time for discussion so participants do not feel rushed.

- After the pilot, get agreement on how the governance team wants to finish scoring projects. Some teams will want to continue scoring as a group; others may want to do their scoring in advance and come prepared to discuss.

- Take time to review and validate consistency of scores: some governance team members may be surprised about the scores of certain projects. It is not unusual for some medium and high scoring to be inconsistently applied. The group may have determined that a project was a “high” in one case but after review, it should really be a “medium” or vice versa.

In the next post we will cover the relationship between priorities and resources and the need to reinforce over-communicating priorities and how this affects resource allocation.