Two Simple Questions

You can measure your general portfolio health with two simple questions:

1) Do you approve all or almost all of your projects?

2) Are you approving so few projects that people would say you are “cutting to the bone”?

These are two portfolio management extremes that we will examine in this post.

Approving Everything is Bad

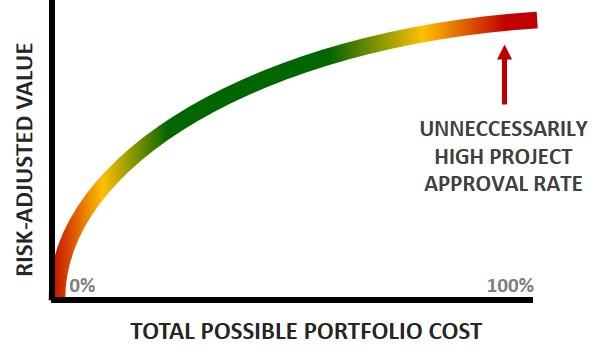

Question number one highlights a common trap for many companies, approving all or almost all projects that get reviewed. This indicates that the project selection process is not working well. When governance councils have a project approval over 90%, it means very few projects are getting screened out and some poor projects are probably getting approved. Approving nearly all projects also means that significant diminishing returns kick in for this group of projects and executing this work likely requires unnecessary multi-tasking and exceeding the resource capacity of critical resources. While it is theoretically possible for an organization to do an outstanding job of selecting the best possible project candidates upfront and still have a high approval rate, I doubt this occurs very often. More likely, organizations operate in a reactive mode and approve projects as they get proposed; since most projects look good by themselves and almost always have a good reason for getting initiated, the project gets approved and funded. Therefore, one of the best portfolio governance council metrics to measure portfolio health is the project approval rate. We can illustrate these concepts with the graphic below.

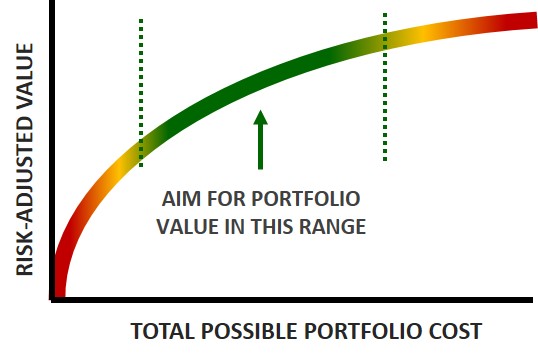

Here we have a bounded curve of possible portfolios (in this case we can apply the cumulative frontier, which is the cumulative portfolio value based on the rank order of projects in the portfolio, not to be confused with the efficient frontier which is based on portfolio optimization). At the upper far right is the problem area in question. If organizations are approving most projects it means there is little to no discrimination among projects which is a symptom of not having enough project candidates to review and stems from poor ideation, work intake, and weak phase-gate processes.. When organizations have more project candidates than they can reasonably take on, the governance council is pushed to do a better job of selecting projects. Organizations can still do a poor job of selecting projects (or may simply ignore resource capacity and continue approving everything) even when they have more than they can take on, but the emphasis here is on increasing the project pipeline so that the governance council will become less reactive and more proactive and say no to projects that really should be screened out. Creating a strategic roadmap to identify important projects (top-down approach) combined with an employee ideation (process bottom-up approach) will help build up the pipeline of projects and increase the decision making rigor by the governance council.

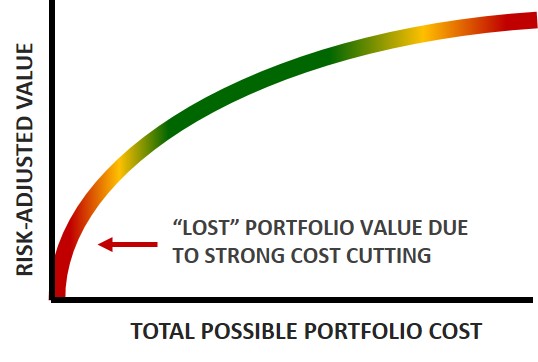

Don’t Cut to the Bone

We can also evaluate portfolio health by looking at the other extreme where an organization is cutting costs so much that any further cuts will hurt the organization’s day to day operations (aka “cut to the bone”). In one place I worked, the cost-cutting measures had been in place for years and a number of good project candidates were hardly under consideration because funds simply were not available and a buildup of project requests was accumulating. A few high value projects got approved, but “money” was left on the table as a result of not taking action on those good project candidates. In some cases, the rigor to do a good cost-benefit analysis is absent and makes it difficult to communicate how much ‘value’ is being ignored by not taking on additional projects due to strong cost cutting measures. Such extreme cost cutting also has the negative residual effect of discouraging innovation among employees. We can also illustrate this with the same graphic.

Summary

In short, asking simple questions about the approval rate of projects and the cost-cutting measures of an organization can highlight general portfolio health. In both cases, organizations should be pushing toward the middle. Adding more project candidates will help ensure that only the most valuable projects get approved. In the case of extreme cost-cutting, companies should improve their ability to measure project value in order to communicate the ‘value’ left on the table. This is best accomplished when a company is doing reasonably well and not when the company is truly in dire straits. Cutting costs “to the bone” is never a good way to stimulate innovation, therefore careful attention is needed when companies are cutting costs too much and not investing in the future.