PRIORITIZATION IN THE CONTEXT OF PROJECT PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

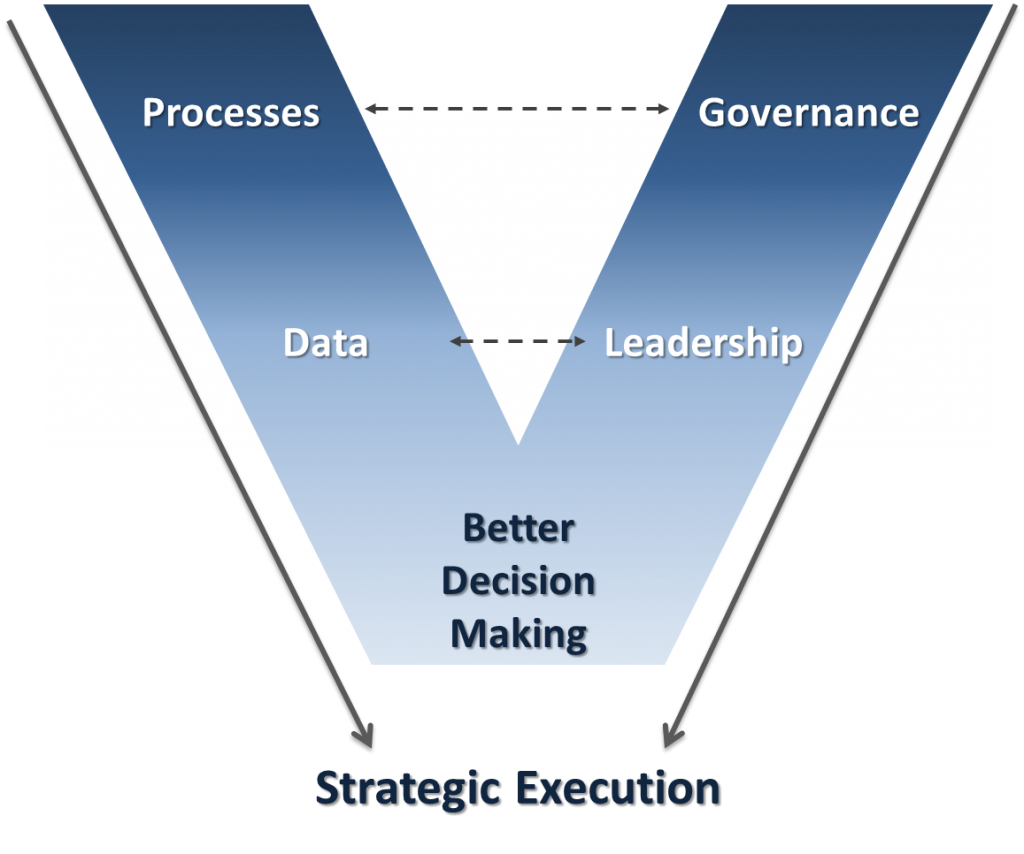

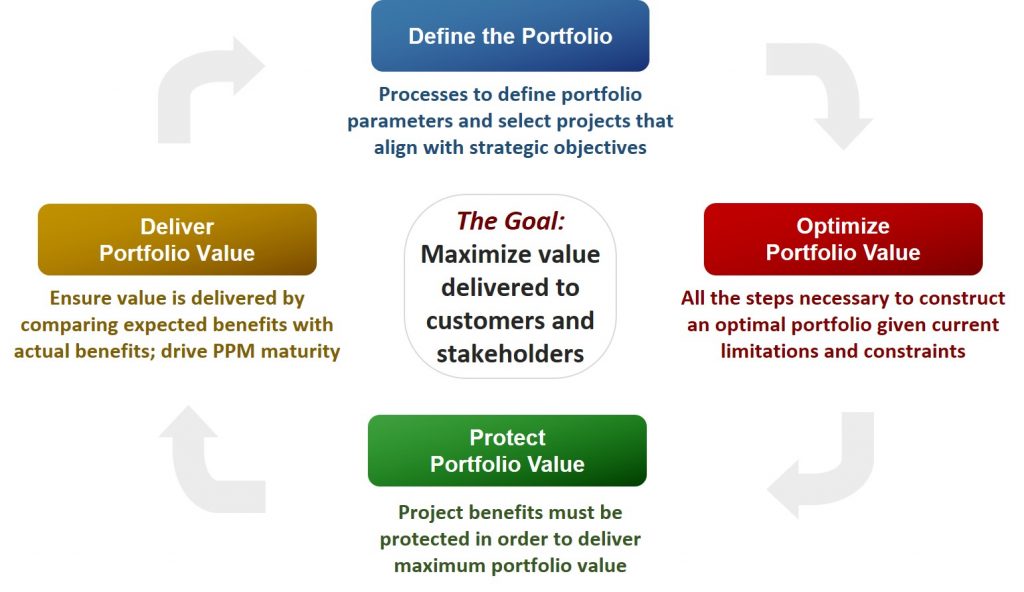

Portfolio management is about maximizing organizational value delivery through programs and projects. In order to maximize value delivery, the governance teams that approve work and prioritize projects need to share a common view of “value” in order to use a scoring model to select the most valuable work and assign the right resources to that work. Understanding the relative “value” of each program and project in the portfolio is at the heart of portfolio management and determines what work is selected, how it is prioritized, where resources are allocated, etc. In order to select a winning portfolio, every governance team needs to share a common understanding of value; without it, you’ll fail to realize the benefits of your portfolio.

However, the definition of “value” will differ at every company because every company has different strategic goals, places varying emphasis on financial metrics, and has different levels of risk tolerance. Furthermore, even within a company, each department may interpret the strategic goals uniquely for their organization. Hence, “value” is not clear cut or simple to define. Any organization that manages a portfolio of projects needs to define and communicate what kinds of project work is of highest value.

The Scoring Model is the Prioritization Tool

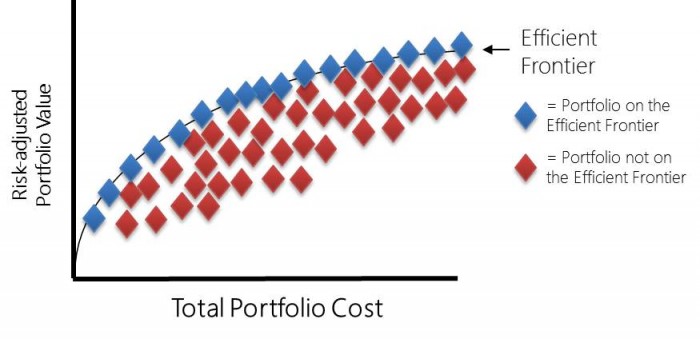

The tool for assessing project value is a scoring model, which includes the criteria in the model, the weight (importance) of each criterion, and a way of assessing a low, medium, or high score for each criterion in the model. A good scoring model will align the governance team on the highest value work and measure the risk and value of the portfolio. A poor scoring model will not adequately differentiate projects and can give the governance team a false precision in measuring project value.

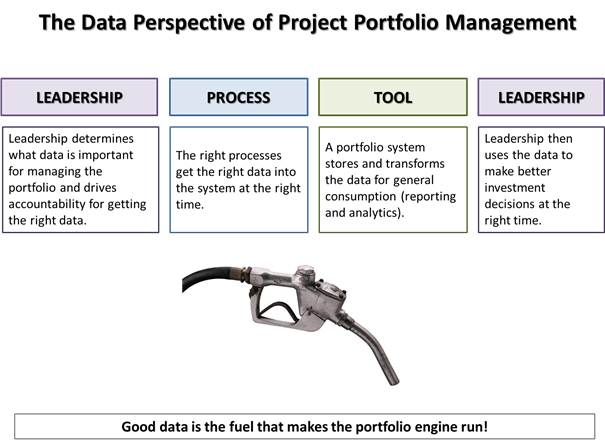

In the context of the portfolio lifecycle, assessing project value is particularly important in the first two phases: Define Portfolio Value and Optimize the Portfolio. When evaluating new projects for inclusion in the portfolio, the governance team must understand the relative value of the proposed project in relation to the rest of the projects in the portfolio; this will help inform the governance team’s decision to approve, deny, or postpone the project. Once there is an established portfolio, the same value scores can be used to prioritize work within the portfolio. For many organizations, the process of selecting projects and prioritizing projects is merged together to develop a rank order list of projects where the governance team “draws the line” where budget or resources run out is an acceptable way to define the portfolio. Unfortunately, this approach does not result in an optimal portfolio, but is acceptable for lower maturity organizations. Strictly speaking, we should distinguish portfolio selection from project prioritization and for the purposes of this post we will focus strictly on using the scoring model for prioritization.

Gaylord Wahl of Point B Consulting says that priorities create a ‘true north’ which establishes a common understanding of what is important. Without a clear and shared picture of what matters most, lower-value projects can move forward at the expense of high-value projects. Even though experienced leaders understand the need to focus on a select group of projects, in practice it becomes very difficult. Good companies violate the principal of focus ALL THE TIME and frequently try to squeeze in “just one more project.”

Prioritization is About Focus

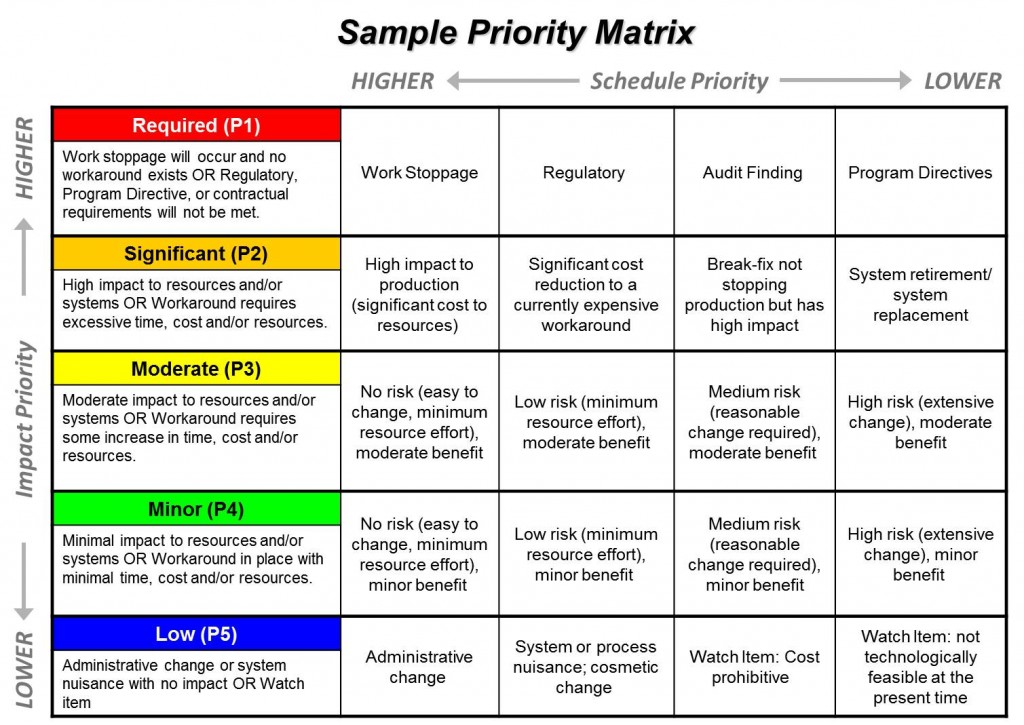

Prioritization is about focus—where to assign resources and when to start the work. It enables the governance team to navigate critical resource constraints and make the best use of company resources. Higher priority projects need the best resources available to complete the work on time and on quality. Resources that work on multiple projects need to understand where to focus their time. When competing demands require individuals to make choices about where to spend their time, the relative priorities need to be obvious so that high-value work is not slowed down due to resources working on lower-value work. You have to be sure that your most important people are working on the most important projects so that you can get the most important work done within existing capacity constraints.

Furthermore, when resources are not available to staff all of the approved projects, lower priority projects should be started later once enough resources are freed up to begin the work. However, not all projects can be initiated immediately. Understanding relative priorities can help direct the timing and sequencing of projects. In some cases, high priority projects may have other dependencies or resource constraints that require a start date in the future. In other cases, lower priority projects get pushed out into the future. In both cases, schedule priority helps answer the question “when can we start project work?” Remember, prioritization is about focus—WHERE to assign resources and WHEN to start the work.

BUILDING THE SCORING MODEL

Assessing project value is at the heart of portfolio management, and the scoring model is the tool to help assess value. Therefore, building a good scoring model is integral to prioritizing work. In fact, as we will see, prioritizing the criteria in the scoring model is a major component of the prioritization exercise.

Step 1 – Define the Scoring Criteria

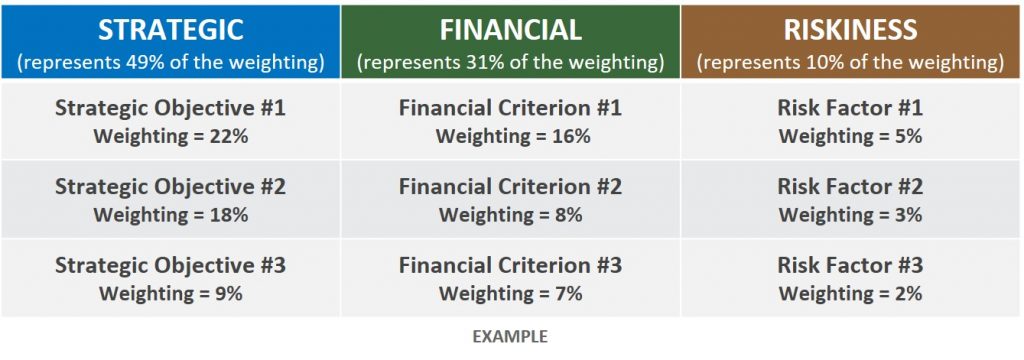

The first step in building the scoring model is to identify and define the criteria in the model. In the past, expected financial benefits would be a singular way of measuring project value. Although this is a tangible and quantitative way to measure value, experience shows that merely selecting and prioritizing work based on financial benefits fails to yield optimal strategic results. In high performing organizations, value can include intangible (qualitative) factors such as the degree of strategic accomplishment, customer impact, and organizational benefits. Therefore, we recommend a combination of quantitative and qualitative criteria. At the very least, your scoring model should include three categories of criteria: strategic alignment, financial benefit, and risk. This is your highest tier of scoring criteria (what we will refer to as “tier 1” criteria). Within each of these categories are the sub-criteria that will actually be used to evaluate projects (referred to as “tier 2” criteria). Why are two tiers of criteria needed? Let’s look at the strategic category. Some organizations simply want to evaluate the degree of strategic alignment, but since nearly all organizations have two or more strategic objectives, for the purposes of assessing project value, you should evaluate the degree of alignment across all of your strategic objectives. Projects that positively impact multiple strategic objectives are generally more valuable. In addition, having a discrete understanding of which strategic objectives each project supports will further enable the governance team to prioritize work. Each strategic objective is a sub-criterion (tier 2) used to assess project value. The three recommended scoring model categories are defined below.

Strategic Criteria: Portfolio management is focused on strategic execution, so measuring strategic alignment as part of your scoring model is important. This would include your organization’s strategic objectives.

Financial Criteria: All for-profit companies should incorporate financial benefit into the scoring model such as net present value (NPV), return on investment (ROI), payback, earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), etc.

Risk Criteria: Finally, a good scoring model takes into account the risk factors of the project. These are not individual projects risks, but a measure of the “riskiness” of the project. Just like a stock portfolio, each investment carries a different level of risk. Remember, if you could only choose one of two investments that each have the same return, you will always go with the least risky option.

Step 2 – Prioritize the Criteria

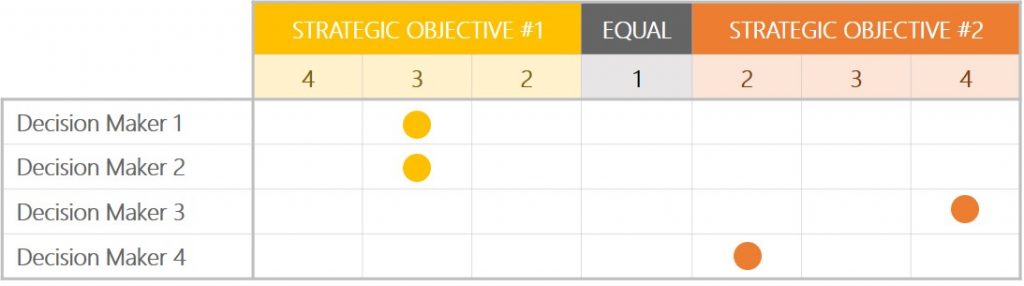

The second step is to prioritize the criteria from step 1. This is best done using pair-wise evaluations, a simple method of comparing two criteria against each other (also known as the Analytic Hierarchy Process, or AHP). This is easily accomplished in one on one sessions with each decision maker. This evaluation is perhaps the most important step in the entire process because it will not only determine the weighting of your scoring model, but even more it will test and ultimately align the governance team’s understanding of the organizational strategies. For example, when evaluating strategic criteria, the governance team will be asked to compare strategic objective 1 against strategy objective 2. On paper, everyone probably understands why each strategic objective is important but has probably not considered the relative importance of one strategic objective compared to another. Using AHP will force each person to really consider whether the two strategic objectives are equally important or whether one is truly more important than another (when making comparisons using AHP, a criterion can be equal to, twice as important, three times as important, four times as important, etc. to the other criterion). In the example below, Decision Maker #1 believes that strategic objective #1 is three times more important than strategic objective #2.

Step 3 – Review and Validate

The third step is to review the evaluations as a team. This exercise really highlights what is most important to each member of the governance team and affords a way for the governance team to have a common understanding of value. It is necessary to highlight where the biggest gaps are between the members of the governance team and discuss why each person holds their view. In this discussion, no one’s evaluation is right or wrong, but in the discussions as a governance team new information may come to light that helps everyone align to a common understanding of each strategic objective, financial criteria, and risk criteria. Based on experience, the strategic alignment discussion is of critical importance and can surface divergent views that would never have come to light without the pair-wise exercise. Without going through this exercise, it is impossible to determine if the scoring model truly represents the governance team’s understanding of value.

An example of a single comparison is shown below. In this example Decision Makers 1 and 2 believe that the first strategic objective is three times as important as the second objective. However, Decision Makers 3 and 4 believe that the second objective is four times and two times as important respectively. This governance team needs to come back together to discuss the discrepancies. The true benefit of this exercise is in the discussion that helps align the team to a common view of strategic value.

WARNING: It is tempting to skip these steps by arbitrarily picking scoring weights in order to quickly score and prioritize projects. One large company wasted hours in weekly steering committee meeting debating the weighting of each criterion. In the end, the excessive discussion wore down the committee; it did not produce the right discussion. Rather, focus on the relative value of each criterion compared to other criteria; the weighting will be a mathematical output of the pair-wise comparisons. Additionally, if the governance team does not share a common understanding of value, the benefits of going through any prioritization exercise are greatly diminished and can cause more churn in the long-run. Based on experience with Fortune 500 companies, the pair-wise discussions are not only more effective but also more efficient (a single person can complete their evaluations in 15 minutes). The benefit is in the discussion among the governance team members to align on the criteria for evaluating project value.

By this point, the result of prioritizing the criteria is:

- A governance team that has been calibrated around how to define value

- A scoring model with criteria and weighting that has been validated by the governance team and can be accurately used to assess project value.

The simple example below shows what the weighting could look like after prioritizing the criteria.

In this post we have covered how to purposefully build a scoring model. The next post will cover the remaining steps in order to evaluate and score projects.

The scoring model is a tool for evaluating project value. It is composed of multiple criteria to assess project value. The final score represents the numeric value of the project and can be used to compare against other projects within the portfolio.