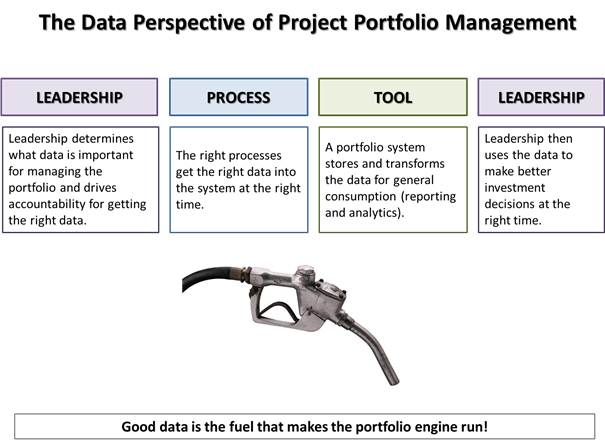

Portfolio management systems have a very real place in making PPM processes successful. These systems have the potential to drive value in a number of ways, some of which are highlighted below:

1) Enterprise repository (“single source of truth”)—having a single system that contains up-to-date and accurate project and portfolio data is valuable. Gone are the days of maintaining multiple versions of static Excel files that contain the current “authorized” list of projects. This value is magnified the easier it is to access the system and the greater the number of users who access the system.

2) Process enabler—on top of merely storing project and portfolio data, portfolio management systems can better enable portfolio processes through workflow automation. This is particularly useful for stage-gate project reviews that have a number of review steps and need approval by multiple parties. Portfolio management system can also better enable project management and capacity management processes. Thus the tool reduces the amount of work needed to carry out these processes, reducing lead time and costs.

3) Portfolio tools—portfolio management systems commonly come with tools that make portfolio management easier overall. One clear example is portfolio optimization, which is difficult (if not impossible) with spreadsheets and other databases. Portfolio management systems can make this otherwise difficult job easier by providing the tools needed to effectively get the job done.

4) Reporting and analytics—one of the greatest benefits of utilizing portfolio management systems is to get accurate and up-to-date reports on the status and health of projects, programs, and portfolios. Buying a portfolio management system and not utilizing the reporting capabilities or analytics is like buying a car with only two gears—you’ll make progress but not as quickly as you will by providing decision makers with insightful information and up-to-date reports.

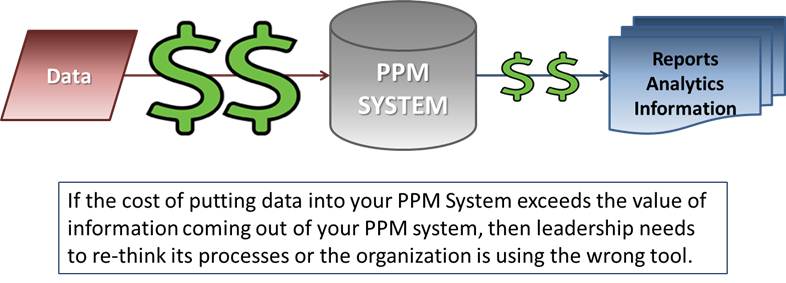

The critical question then is, “how much value are you getting out of your portfolio management system?” If the cost of the system plus the cost of entering data plus the cost of maintaining the system exceeds the value of the information coming out of it, senior leadership either needs to reconsider its ways or change its portfolio management system.

As we discussed in an earlier post, leadership plays a huge part in making sure the right data gets fed into the system at the right time. Yet, leadership plays just as big of a role in making sure the organization gets value from its portfolio management system. Let’s quickly review the four areas where companies can derive value from portfolio management systems and the potential risks.

1) Enterprise repository—if employees and managers do not access the system often, or if there are competing places to get similar project and portfolio data, the system loses value.

2) Process enabler—if project and portfolio processes are not regularly followed, then the effort to load the system with data to enable those processes is a waste of time.

3) Portfolio tools—if the organization does not leverage the tools available in its portfolio management system, then it paid extra money for tools it doesn’t use.

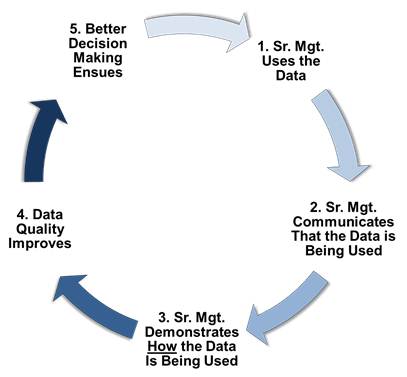

4) Reporting and analytics—if senior management does not pull reports and use the data, then all the effort to ensure that quality data is going into the system is a waste of time. Even worse, if management does not communicate that it uses the data and demonstrate how it uses the data, the organization easily becomes skeptical of the value of portfolio management.

What value do you currently get from your portfolio management systems? Have you encountered any of the problems mentioned above?