In our hyper-accelerated business world, data analysis and data visualization are exceptionally important. In the realm of project portfolio management (PPM) and PMO’s, organizations need robust data analysis to strengthen decision making and improve strategic execution. The key is to have the right processes in place to collect the right data and ensure that the data is of good quality. As I have said before, data collection is not free; any data that is collected but not actively used is a waste of organizational resources. Knowing what information is needed to drive better decision making will help ensure that only important data is collected. Therefore, organizations should wisely consider what metrics, analytics, and reports are most important to senior leaders and then develop or improve the processes that drive the collection of that data. The power of having good portfolio data is to conduct strong portfolio optimization.

3 LEVELS OF ANALYSIS

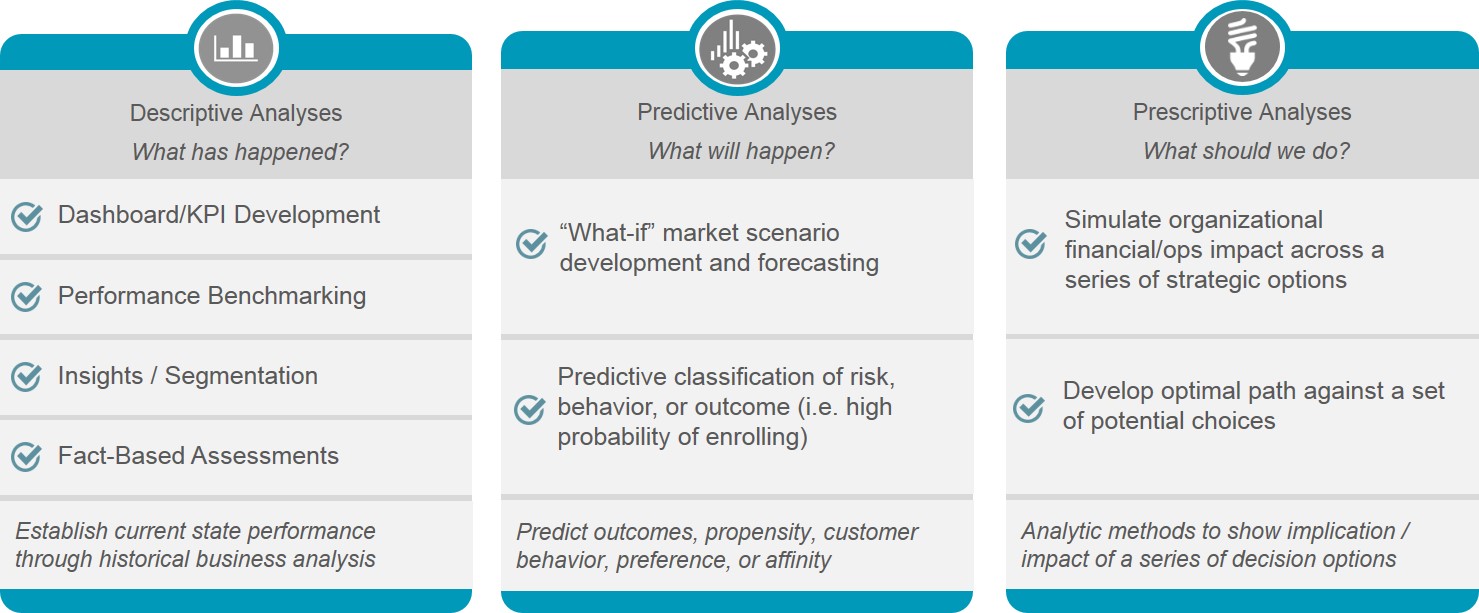

Once organizations have a stable foundation for PMO/PPM data collection, they can embark on the data analysis journey. The graphic below highlights three levels of data analysis:

- Descriptive analysis—this helps answer the basic “what has happened?” This level of analysis is the most basic as it is fact-based and is required for developing key performance indicators and dashboards.

- Predictive analysis—this helps answer a more important question, “what will happen?” With sufficient data, organizations can begin to predict outcomes, especially related to project risk and project performance and the impact to project delivery as well as the portfolio as a whole.

- Prescriptive analysis—this helps answer a more difficult question “what should we do?” This requires more detailed and advanced analysis to determine the optimal path against a set of potential choices. Prescriptive analysis of the portfolio provides significant benefits by enabling organizations to choose the highest value portfolio and choose a group of projects with a higher likelihood of success.

PORTFOLIO OPTIMIZATION

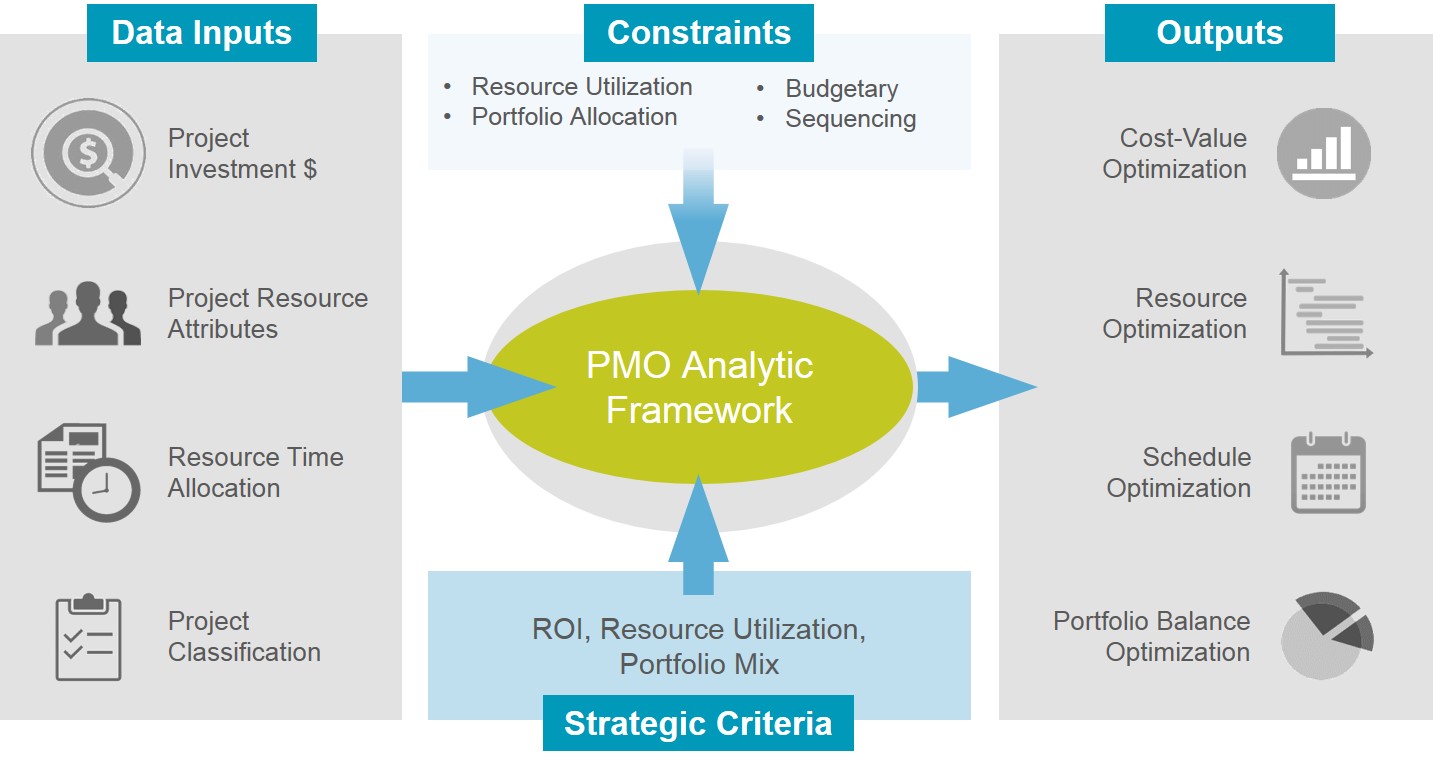

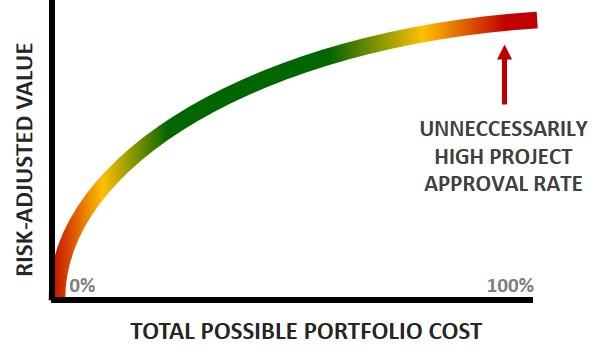

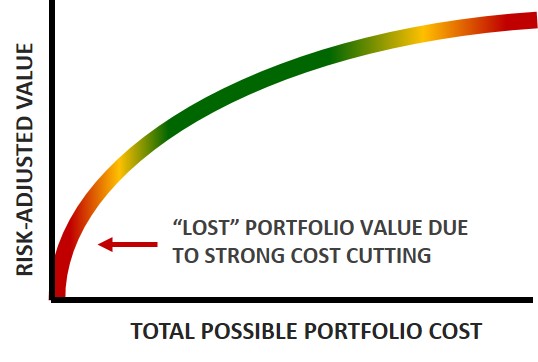

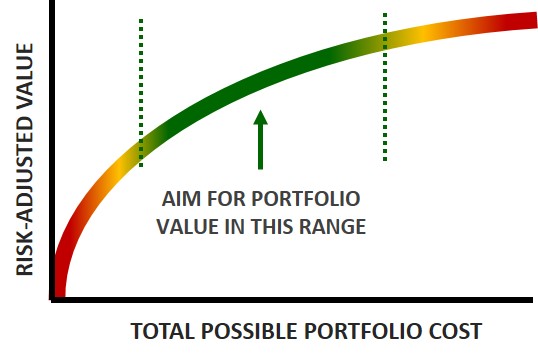

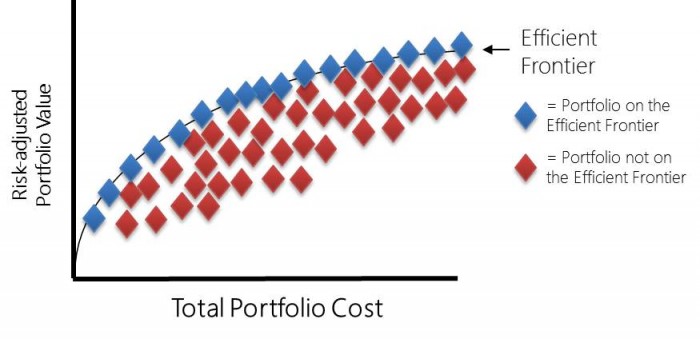

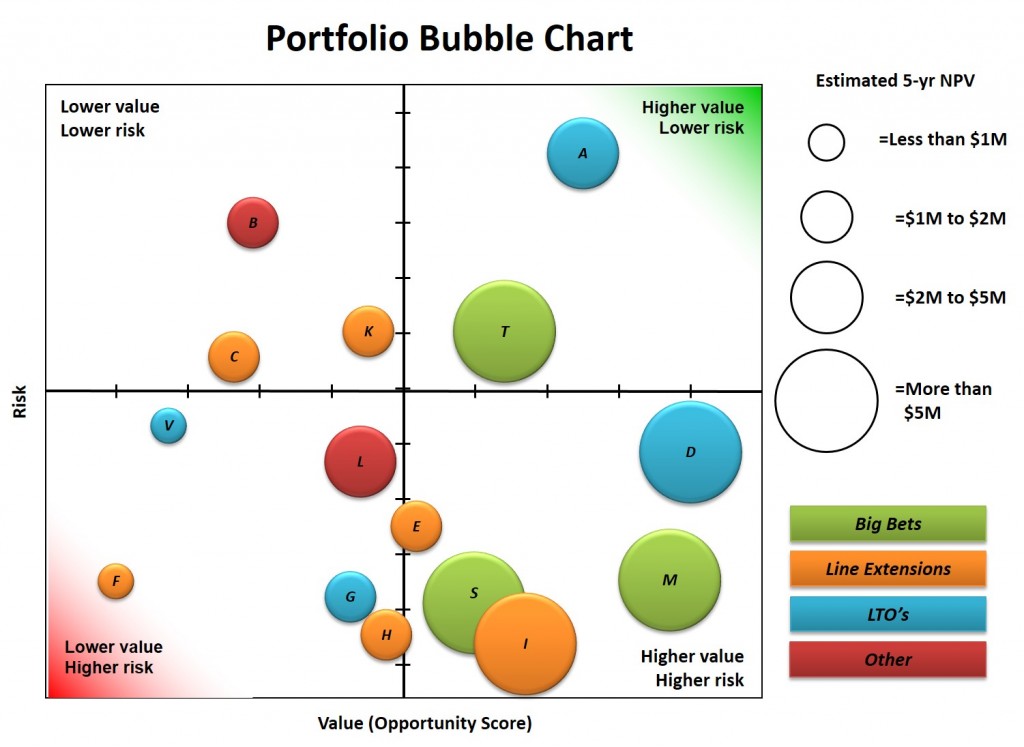

Portfolio optimization is major part of the prescriptive analysis described above. Organizations should endeavor to get to this point because it delivers substantial value and significantly improve strategic execution. In order to optimize any part of the portfolio, organizations must understand the constraints that exist (e.g. budgetary, resource availability, etc.). These constraints are the limiting factors that enable optimal scenarios to be produced. There are four basic types of portfolio optimization described below:

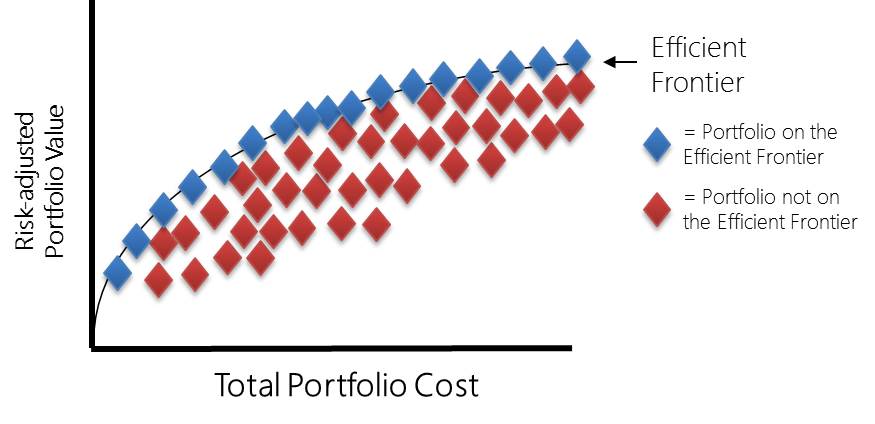

- Cost-Value Optimization: this is the most popular type of portfolio optimization and utilizes efficient frontier analysis. The basic constraint of cost-value optimization is the portfolio budget.

- Resource Optimization: this is another popular way of optimizing the portfolio, and utilizes capacity management analysis. The basic constraint of resource optimization is human resource availability.

- Schedule Optimization: this type of optimization is associated with project sequencing, which relates to project interdependencies. The basic constraints of schedule optimization are project timing and project dependencies.

- Work Type Optimization: this is a lesser known way of optimizing the portfolio, but corresponds to a more common term, portfolio balancing. The basic constraints of work-type optimization are categorical designations.

APPROACH

The following diagram summarizes the above points and highlights how having the right data inputs combined with constraints and other strategic criteria can produce optimial outputs across four dimensions of portfolio optimization.

Point B Consulting’s 5-step methodology for conducting PMO analytics enables organizations to realize the full potential of their analytic processes.

- Define: Determine the performance criteria for measuring PMO/PPM success and develop a set of questions / hypotheses for further modeling and investigation

- Transform: Gather and transform all available resource, project, business data for further visualization and analysis

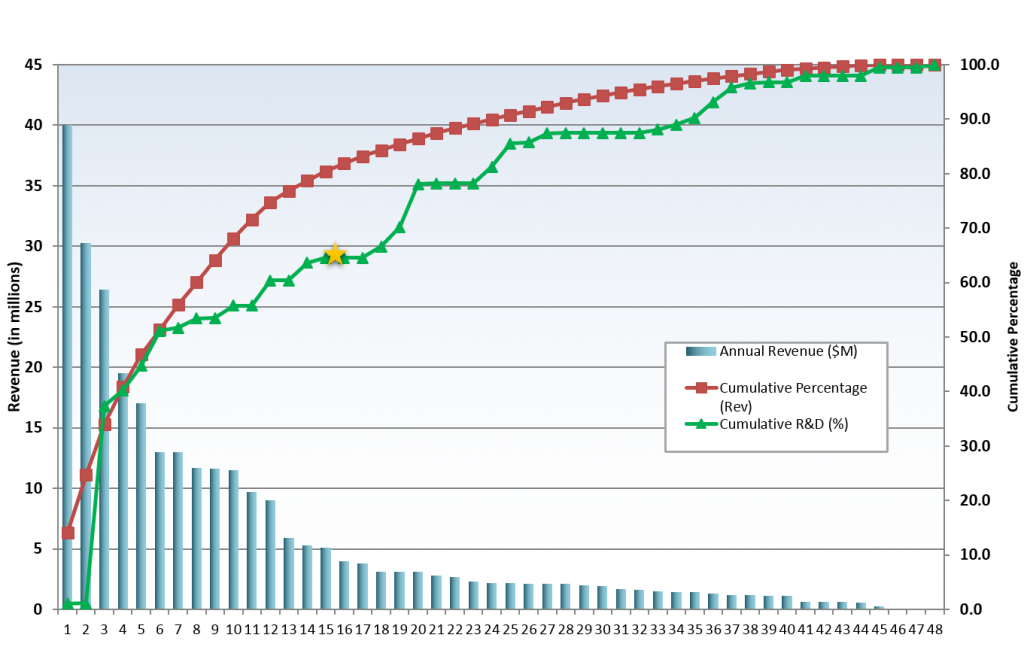

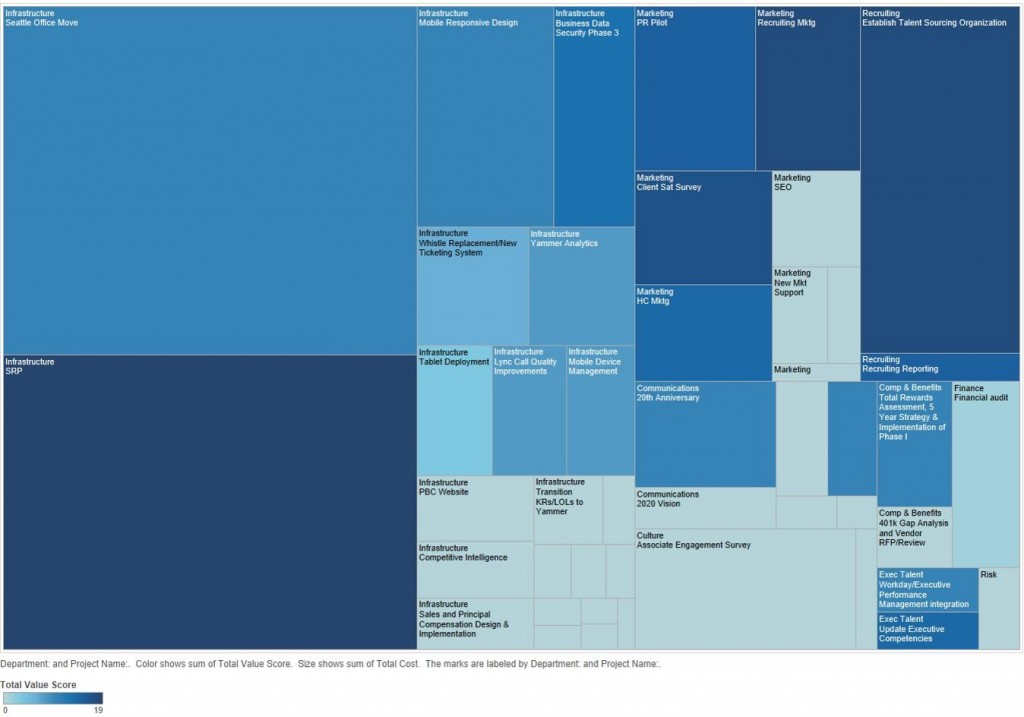

- Visualize: Inventory all projects with related resources and highlight key trends/insights based on project and business data

- Evaluate: Develop analytic framework to test, adjust, and optimize against tradeoffs between project sequencing, resource allocation, and portfolio value

- Recommend: Develop a final set of project prioritization recommendations for desired future state

In summary, portfolio optimization delivers significant strategic benefits to any organization, but getting the right processes in place to collect good data is not easy. Having the right data can enable your organization to know what is happening to the portfolio (descriptive analysis), what could happen (predictive analysis), and what senior leaders should do (prescriptive analysis).