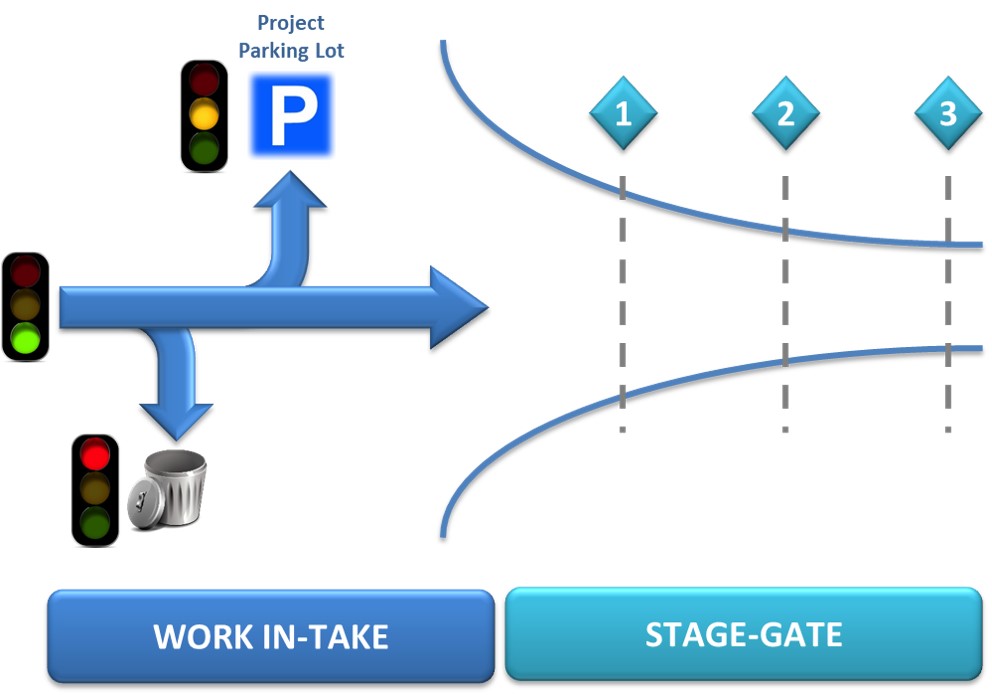

What is the difference between a work intake process and a Stage-Gate process? This is important to distinguish, especially for newer PMO’s that are setting up portfolio management processes.

Work Intake

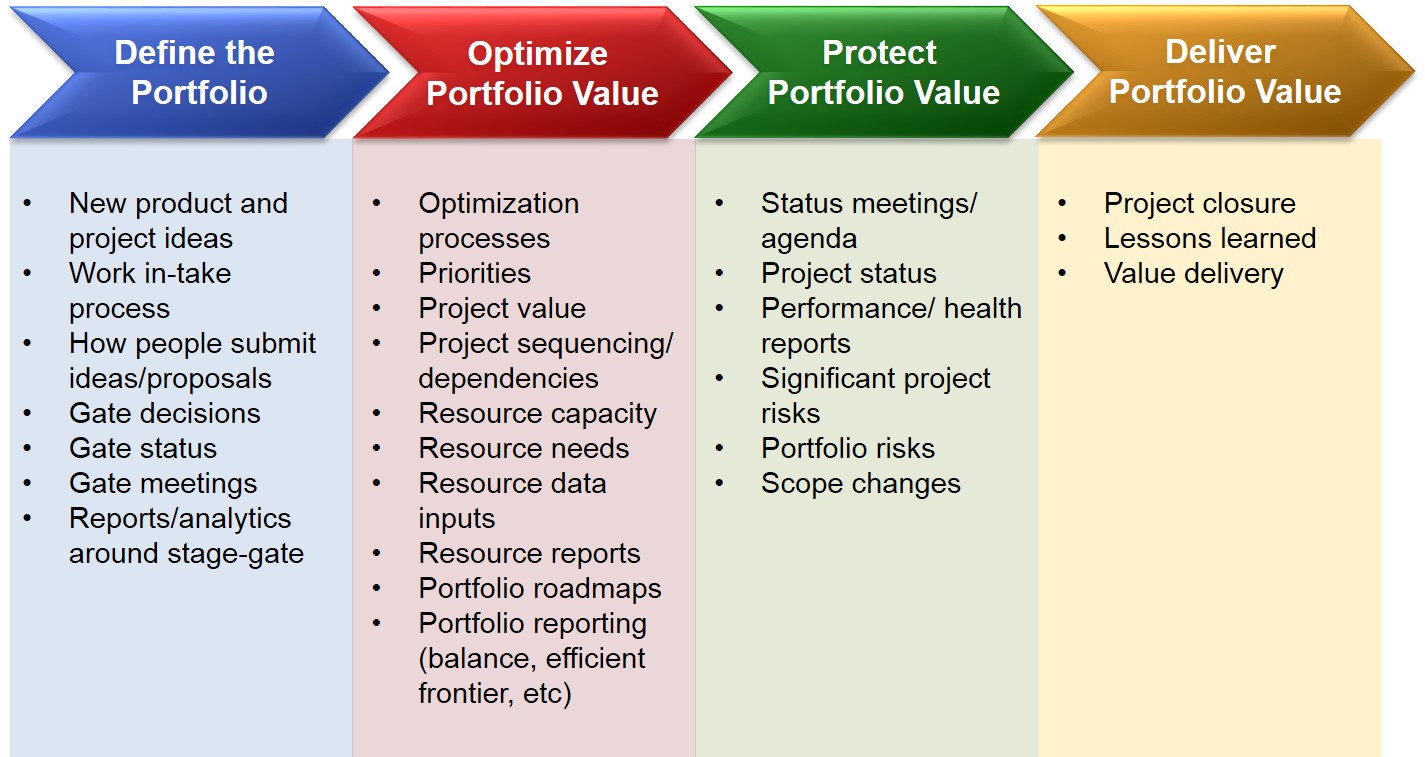

The work intake process refers to the steps of developing a project proposal and bringing it to the governance board (or PMO) for a go/no-go decision. This process works in conjunction with Stage-Gate, but can also be a standalone process. When PMO’s are first established, an intake process needs to be defined so that the PMO can manage incoming project requests. Once the portfolio governance team is established and familiar with the intake process, a full Stage-Gate process should be developed.

The work in-take process is important so that all project proposals are created in a consistent manner with common tools and processes.

The unintended consequences of not having a work in-take process include:

- Organizational confusion—employees will be unclear on how project proposals get brought forward, resulting in fewer project proposals from within the organization

- Time delays—without a clear understanding of the process, project proposals may be unnecessarily delayed from being reviewed

- Quality erosion—the quality of the proposals may erode and further delay the process since participants may not be aware of the information needed for project reviews.

In order to have a successful work in-take process, all of the roles and responsibilities of each participant in the process needs to be documented and communicated. Some questions that need to be answered include: who will write the proposal (project manager, business analyst, executive sponsor)? What information is needed? What templates need to be filled out? What format must the information be presented? Are there any IT systems that need to be utilized (e.g. SharePoint, portal, portfolio management system)? Are there any time constraints for submitting proposals? Is a presentation needed? Who will make the presentation?

Another important reason to establish a work in-take process is to help control the work in progress (WIP) within the organization. At one Fortune 500 company I worked with there was no “single entry” to the organization. Rather, requests came in through system managers, process engineers, subject matter experts, and other employees. It was nearly impossible to track all of the work being done because there was no “single source of truth”. A lot of shadow work was being done in the organization and it was very difficult to stop it because there was no established or enforced work in-take process. This shadow work eroded portfolio value, took valuable resources away from key projects, and was ‘death by 1000 cuts”.

Work in-take success factors:

- Having a single “front door to the organization”

- Clear roles and responsibilities of all participants in the work in-take process

- Clear understanding of what information needs to be submitted

- Clear communication about the templates and systems need to be used (if applicable)

- Clear timetables for submitting requests and making presentations

Stage-Gate

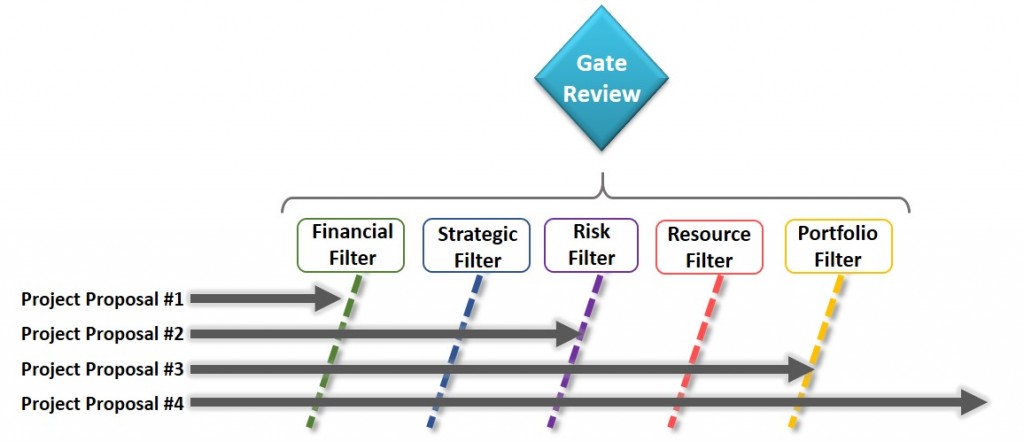

Stage-Gates are a governance structure to evaluate, authorize, and monitor projects as they pass through the project lifecycle. Each gate represents a proceed/modify/hold/stop work decision on the part of the portfolio governance team. Although the Stage-Gate process parallels the project life cycle, the two are not exactly the same. For more information on the project lifecycle please see the Project Management Body of Knowledge Guide 6th Edition (PMBOK) by the Project Management Institute (PMI).

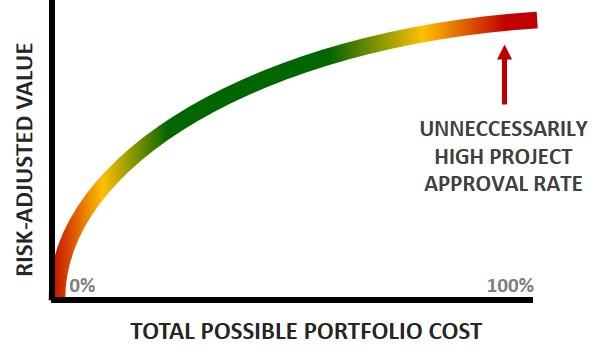

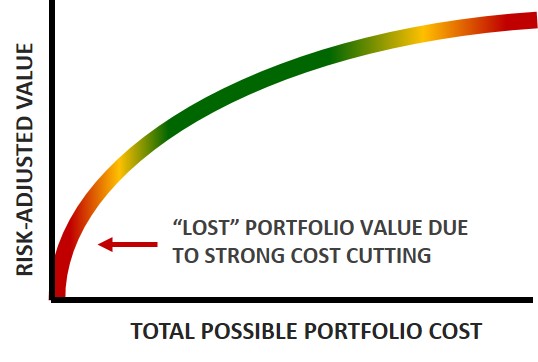

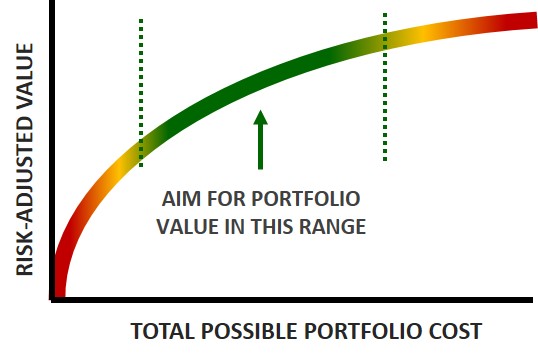

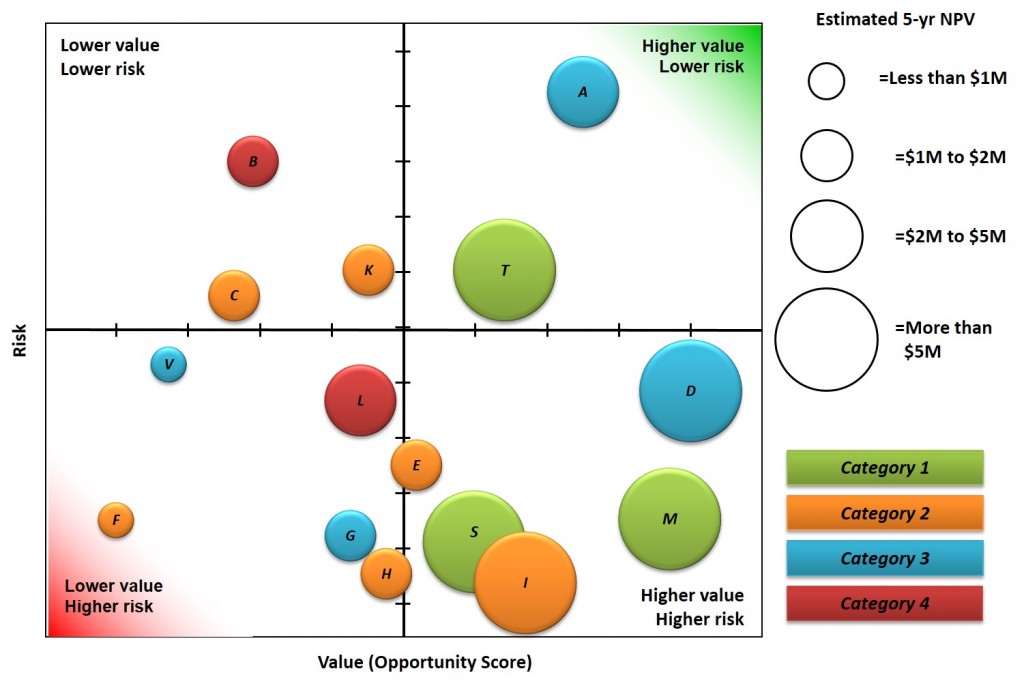

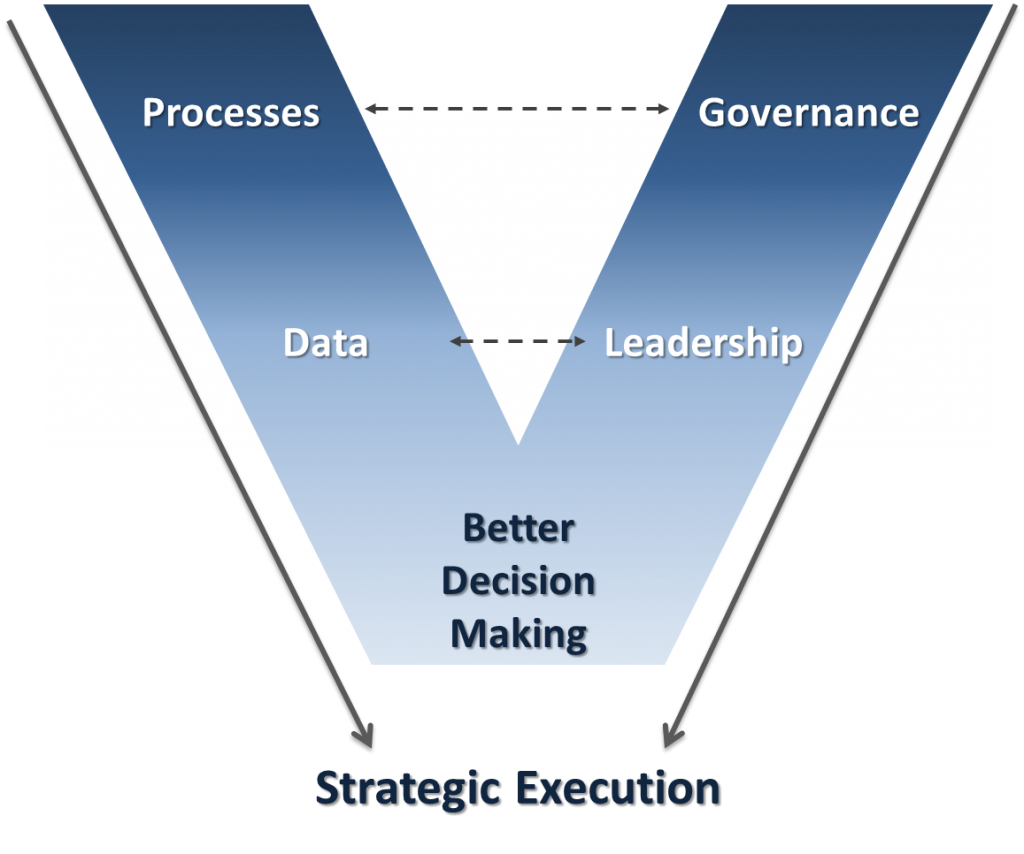

Stage-Gates are a critical component of project selection. A winning portfolio must contain winning projects, therefore the portfolio governance team must be able to discriminate between good projects and great projects. The decision gate process enables the project governance board to review these projects based on predetermined strategic criteria at each gate review of the Stage-Gate process. At each of those gates, important project information is provided to the project governance board to make a go/no-go decision related to the project. Without this mechanism, unnecessary or poorly planned projects can enter the portfolio and bog down the work load of the organization, hampering the benefits realized from truly important and strategic projects.

Conclusion

New PMO’s should start by establishing a work intake process to ensure there is one clear path for project requests to reach the PMO. Later, as the organization adopts the work intake process, a full Stage-Gate process can be added on to increase the quality of project proposals and help ensure the portfolio contains winning projects.